Film Screenings

What's on First

Three different titles had been considered, by different sources, as the inaugural project of the New Wave. Each is the debut feature of its director – directors, in the case of one – and each has its significance to the movement that kick-started a new era of Hong Kong film.

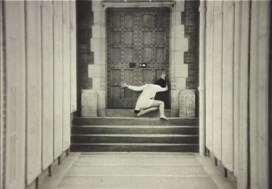

Jumping Ash, co-directed by an ethnic Chinese from England and a former teen goddess of Cantonese cinema, embodies many of the New Wave attributes, yet it was released in 1976, over two years ahead of the late 1970s phenomenon. The Extras was made during the nascent months of the New Wave by a crucial figure of the movement but is very much a commercial project, without much of the characteristic New Wave impulses. Released a few months later, The Butterfly Murders, directed by another key New Wave filmmaker, is marked by many of the movement's defining traits.

Which is the New Wave's first film?

Questioning Genre

The wuxia genre was a staple of Hong Kong mainstream cinema and it's no surprise that two of the New Wave's early key works, Tsui Hark's The Butterfly Murders (1979) and Patrick Tam's The Sword are reactions against it, formally and content-wise. The former is even a much-quoted exemplar.

Violent Encounters

Violence, let's face it, is cinematic. Formally and thematically. Hong Kong in the late 1970s and early 1980s was starting to experience the disillusion and disorientation that often came with prosperity. Violence became a choice vehicle to deliver those sentiments.